Latest survey reveals that our salt intake has not come down in years, as new evidence reinforces the need for salt reduction

Monique Tan, PhD researcher at Queen Mary University of London

In March, the long-awaited survey of salt intake in England was published – which came with disappointing results. Not only is our average salt intake still well above the maximum recommended intakes (by 40%), but it has not declined for the past ten years.1

This means that the downward trend we had observed in our salt intake (as a population) has effectively stalled, and this is disastrous news for public health.

But first, why is salt such a big deal and what action should be taken in achieving salt reduction – the leading cause of raised blood pressure which in turn is the major cause of strokes and heart disease?

Salt is the most unhealthy of our dietary habits

Eating healthily is in fact much less complicated or controversial than what any fad diet would have us believe.

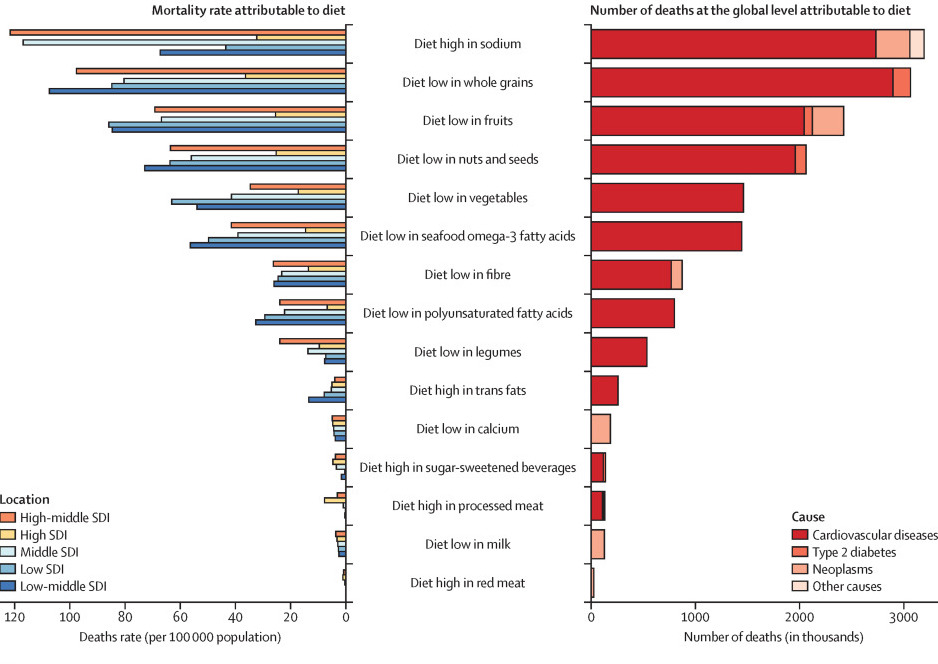

Salt doesn’t seem to be getting much attention lately, but eating less of it could be the single most important dietary habit to preserve our long-term health. It has been estimated that our current high salt intake (which averages at around double the amount we are recommended to eat2) is behind more deaths worldwide than consuming too much soft drinks, dairy, or meat, combined.

Figure 1. Most recent estimates of the number of deaths worldwide attributable to different dietary habits.3

Two major studies were published earlier this year in prestigious scientific journals.4,5 The first demonstrates that all of us would benefit from reducing our salt intake, and the second sheds light on the numerous lesser-known ways in which too much salt can harm us.

Do not wait for high blood pressure to reduce your salt intake

A small number of controversial studies have shaken the world of salt science in recent years, claiming for example that people with normal blood pressure shouldn’t reduce their salt intake.6

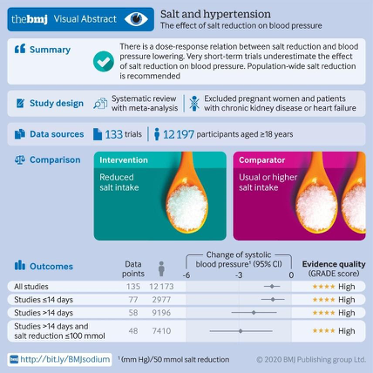

This claim was clearly disproved by the researchers behind the first study published this year.4 Searching for all high-quality studies of salt reduction ever conducted, they found 133 trials, collectively representing about 12,200 participants. We have to appreciate how huge this number is – a single trial rarely recruits more than a hundred participants. Combining all trial results together in a meta-analysis, they came to three important conclusions:

- Eating less salt benefits us all. That is, reducing our salt intake reduces our blood pressure, regardless of sex, ethnicity, and baseline blood pressure. By keeping our blood pressure low, we also are less likely to develop a cardiovascular disease, including stroke and heart disease (which are currently what is causing the most deaths and disability in our world). This means that you should not wait to have high blood pressure (hypertension) to reduce your salt intake.

- The less salt, the better. The researchers confirmed a dose-response relationship, meaning that the more we reduce our salt intake, the more our blood pressure falls. Interestingly, for the exact same amount of salt taken out of their diet, older people would benefit more than younger ones, and people of African, Asian, or mixed ethnicity would benefit more than Caucasians.

- It is a long-term game. When it comes to salt (and anything diet-related), making small changes over a longer period of time goes much further than doing a lot over a few days. For every gram of salt cut out, the effect on blood pressure was double in trials that lasted more than two weeks compared to those lasting less. This is also important because it explains why previous studies that only looked at short-term trials underestimated the benefits of reducing salt intake.

Figure 2. Visual abstract of the meta-analysis.4

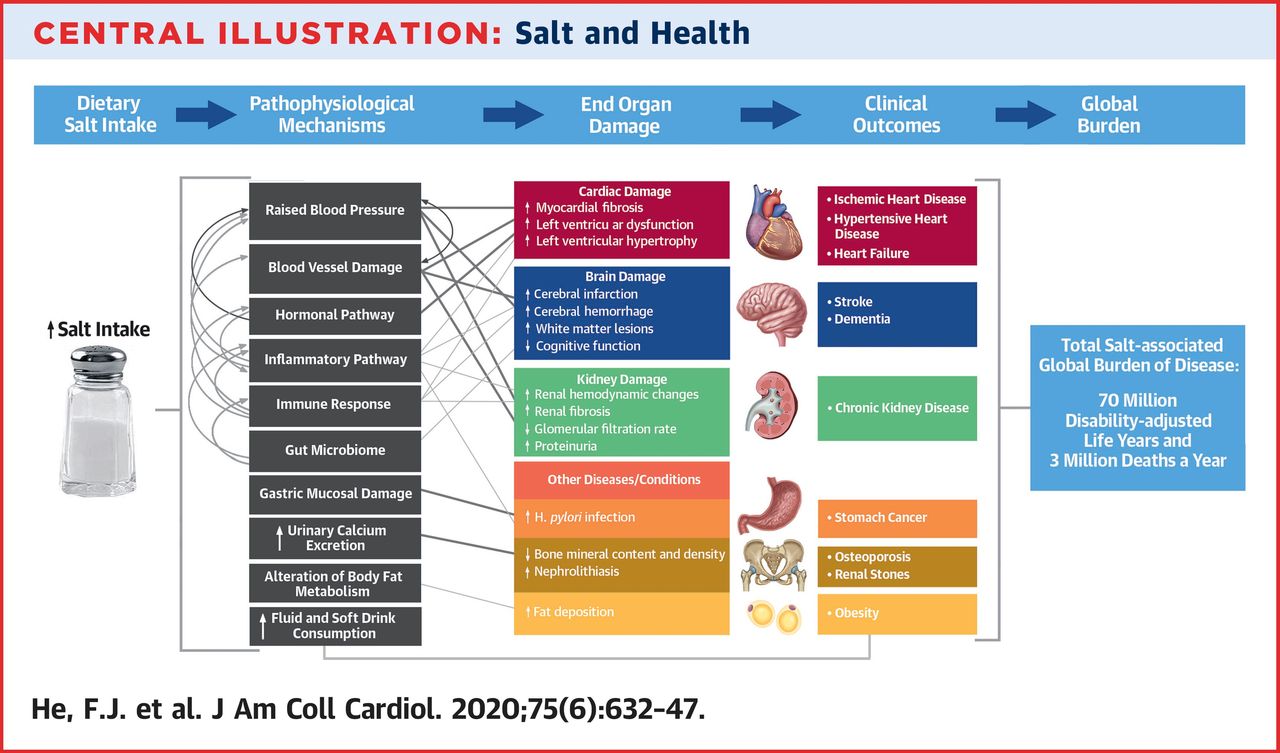

Eating too much salt damages our heart, kidneys, and brain, and also our bones and stomach

The second study was another mammoth undertaking. It summarises all we know about salt and health, ranging from experiments in the 1970s when kidneys were removed from animals to better understand how blood pressure is regulated, to the latest research exploring the links between salt and Alzheimer’s via the gut microbiome.5

A key take-away is the numerous complex and interconnected ways in which salt actually affects our health, in addition to raising our blood pressure and our risk of cardiovascular disease. For example, there are clear links between salt intake and kidney disease, renal stones, osteoporosis, and even stomach cancer. Salt intake could also be somehow connected to weight gain; although this was first thought to be an indirect association via increased soft drink consumption (due to the thirst that comes with eating salt), novel research suggests that salt could have a direct effect on energy and fat metabolism. Links between salt and cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease are also starting to emerge.

Another highlight of this study is how remarkably cost-effective and even cost-saving salt reduction is, as a public health strategy. It was estimated that at a population level, salt reduction would have a similar health impact as reducing tobacco use or obesity. A success story in salt reduction is the case of the UK, where a programme predominantly based on reformulation was pioneered in the early 2000s. By having manufacturers gradually lower the amount of salt they add to their foods over many years, consumers could continue purchasing their favourite products without noticing any taste difference. This programme has led to the salt content of many food products to drop by 15-60% over a decade, resulting in about 9,000 cardiovascular deaths prevented annually, which saves the UK’s health care services about £1.5 billion every year.

Figure 3. The many ways in which salt can harm our health.5

Reducing our salt intake without even realising it

If salt is so dangerous, then why do we all keep eating so much of it?

Because it is hard not to. In high-income countries, about 80% of the salt we consume comes from that added to processed, restaurant, or fast foods (this proportion is still much lower in other countries, but is steadily rising with urbanisation).7-9 This means that we, as consumers, have little control over how much salt we consume.

A diet high in salt also doesn’t come with any obvious symptoms, so many often do not realise they are at risk. Instead, the consequences on our health develop silently over the years, and that’s probably the most insidious thing about it.

The good news is that as a public health strategy, gradual salt reduction can be implemented by the food industry without consumers being aware of any noticeable change to the taste of their food.

In fact , the UK’s salt reduction programme is still regarded as a best practice model to adopt internationally. Key to its initial success was the authorities setting targets for the salt content of specific types of food, and persuading many food manufacturers and retailers to reach those targets within a clear time frame. By gradually and unobtrusively reducing the salt added to our products, the whole population’s palate eventually gets used to a less salty taste. However, recent changes in government policy, muddled responsibilities and industry lobbying have resulted in the UK’s once world-leading salt reduction programme no longer being enforced by its own government.10

Developing, implementing, and sustaining such a programme requires time and coordinated action – which all pays off long term. As the recent evidence based publications demonstrate – reducing salt across the population, even by a small amount, would bring about enormous benefits. Not only is salt reduction affordable, feasible and culturally acceptable – it is also cost-effective and cost-saving. Once the coronavirus pandemic is over, it’s imperative that the UK government revives its salt reduction strategy by enforcing stricter and more comprehensive salt reduction targets - whilst saving thousands of premature deaths each year.

References

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Assessment of salt intake from urinary sodium in adults (aged 19 to 64 years) in England, 2018/19. (Public Health England, London, 2020).

- WHO. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. (World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, 2012).

- GBD Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393, 1958-1972 (2019).

- Huang, L., et al. Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 368, m315 (2020).

- He, F.J., Tan, M., Ma, Y. & MacGregor, G.A. Salt Reduction to Prevent Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 75, 632-647 (2020).

- Graudal, N.A., Hubeck-Graudal, T. & Jurgens, G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev., CD004022 (2017).

- James, W.P., Ralph, A. & Sanchez-Castillo, C.P. The dominance of salt in manufactured food in the sodium intake of affluent societies. Lancet 1, 426-429 (1987).

- Anderson, C.A., et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 110, 736-745 (2010).

- Du, S.N., A.; Batis, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Popkin, B. M. Understanding the patterns and trends of sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium to potassium ratio and their effect on hypertension in China1-3. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 99, 334-343 (2014).

- MacGregor, G.A., He, F.J. and Pombo-Rodrigues, S., 2015. Food and the responsibility deal: how the salt reduction strategy was derailed. BMJ 350, p.h1936.